Either this narrative about weapon stockpiles, being depleted, is part of the information war or Russia is demilitarizing NATO!?!

U.S. and NATO scramble to arm Ukraine and refill their own arsenals

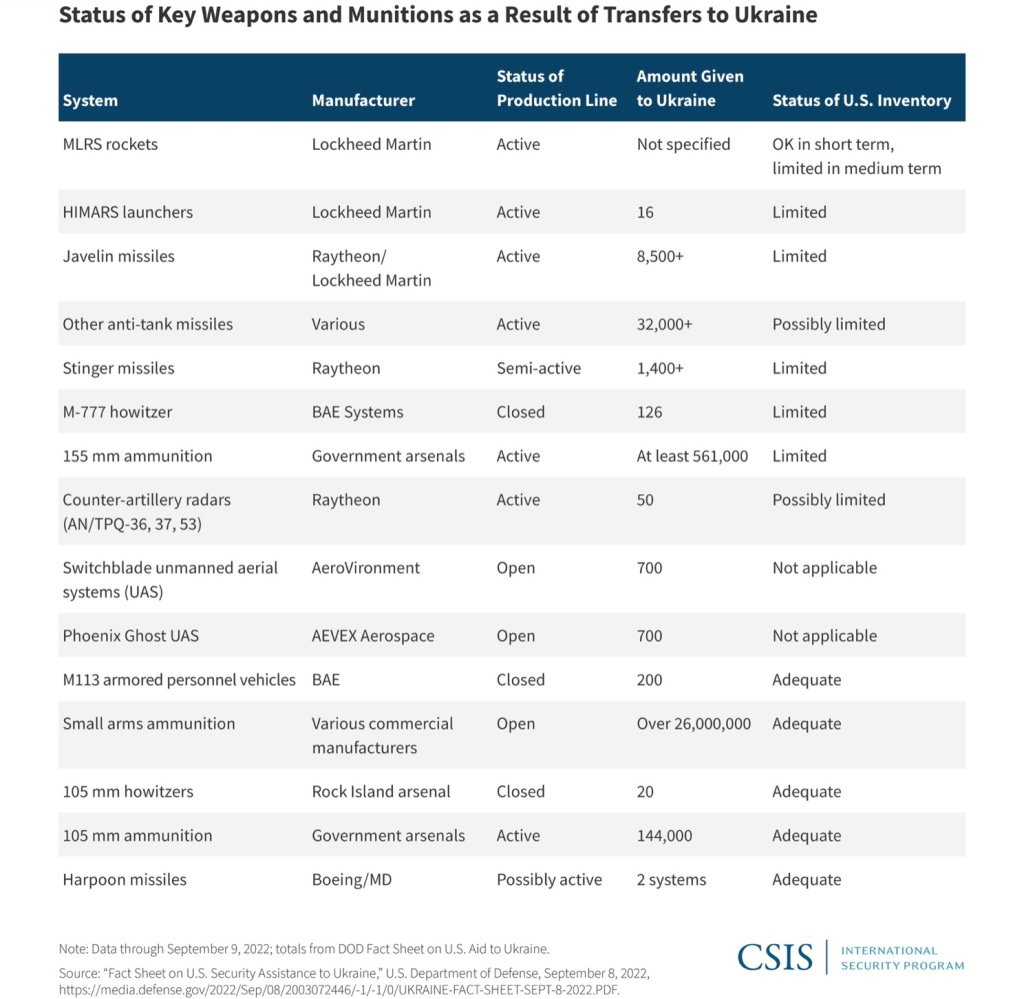

In Ukraine, the kind of European war thought inconceivable is chewing up the modest stockpiles of artillery, ammunition and air defenses of what some in NATO call Europe’s “bonsai armies,” after the tiny Japanese trees. Even the mighty United States has only limited stocks of the weapons the Ukrainians want and need, and Washington is unwilling to divert key weapons from delicate regions like Taiwan and Korea, where China and North Korea are constantly testing the limits.

…

So the West is scrambling to find increasingly scarce Soviet-era equipment and ammunition that Ukraine can use now, including S-300 air defense missiles, T-72 tanks and especially Soviet-caliber artillery shells

…

There are even discussions about NATO investing in old factories in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Bulgaria to restart the manufacturing of Soviet-caliber 152-mm and 122-mm shells for Ukraine’s still largely Soviet-era artillery armory.

…

The European Union has approved €3.1 billion ($3.2 billion) to repay member states for what they provide to Ukraine, but that fund, the [ironically-named] European Peace Facility, is nearly 90 percent depleted.

…

Smaller countries have exhausted their potential, another NATO official said, with 20 of its 30 members “pretty tapped out.” But the remaining 10 can still provide more, he suggested, especially larger allies. That would include France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands.

NATO’s secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg, has advised the alliance — including, pointedly, Germany — that NATO guidelines requiring members to keep stockpiles should not be a pretext to limit arms exports to Ukraine. But it is also true that Germany and France, like the United States, want to calibrate the weapons Ukraine gets, to prevent escalation and direct attacks on Russia.

…

Washington is also looking at older, cheaper alternatives like giving Ukraine anti-tank TOW missiles, which are in plentiful supply, instead of Javelins, and Hawk surface-to-air missiles instead of newer versions. But officials are increasingly pushing Ukraine to be more efficient and not, for example, fire a missile that costs $150,000 at a drone that costs $20,000.

You must be logged in to post a comment.